Interactive Dramaturgies—Media Strategies in Exhibition and Museum Design

H. Hagebölling-Eisenbeis

Interaktive Dramaturgien – Mediale Strategien in der Ausstellungs- und Museumsgestaltung

Interactive Dramaturgies – Media Strategies in Exhibition and Museum Design

In: Kilger, Gerhard ed. Szenografie in Ausstellungen und Museen

Scenography in Museums and Exhibitions

Ed. Klartext, Essen 2004

Republished in:

Kai-Uwe Hemken (HG)

Kritische Szenografie

Die Kunstausstellung im 21. Jahrhundert

Critical Scenography

The Art Exhibition in the 21. Century

Transcript Vlg, Bielefeld, 2015

All rights of his article by the author

The media staging of the object: scenography in exhibition design

The discussion around making scenic elements fruitful for exhibition design can be traced back to the 1970s, when pedagogic approaches emphasised the role of the museum as a communicator. A museum to touch, the breaking down of barriers, opening up to wider sections of society, the consideration of younger visitors, the museum as a place of learning.

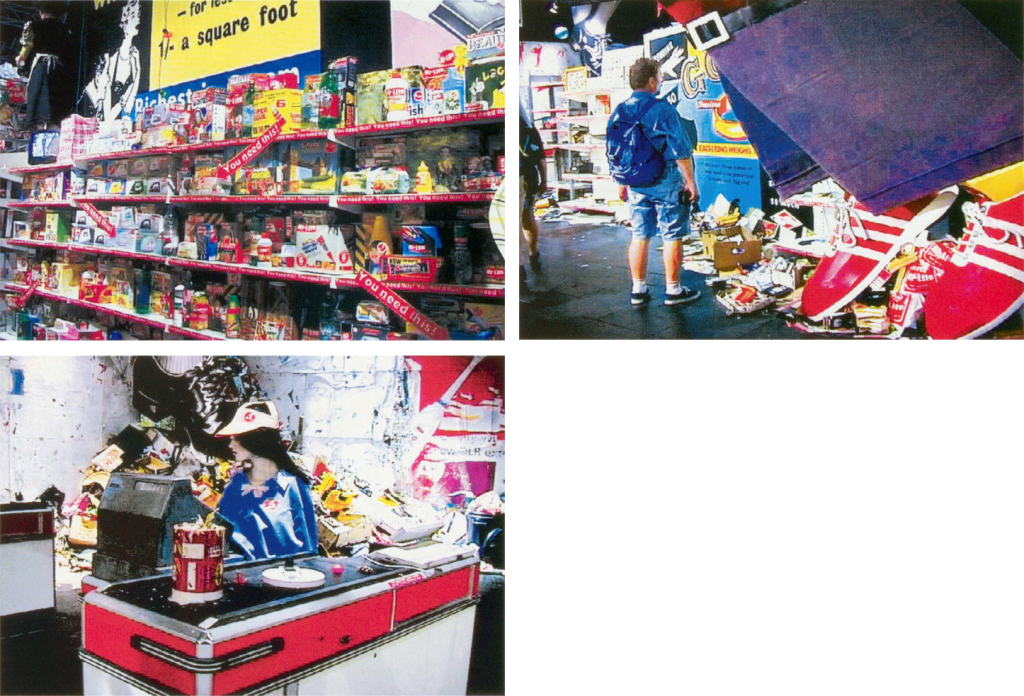

This discussion has continued since then, accompanied by the arguments for and against the inclusion of modern communication technologies and their consequences for the exhibit and its museal values. A theme that has been evidently intensified by event culture and which has gained in topicality, as organisers increasingly focus on the experience and event dimensions of exhibitions and thus clearly follow the newest market research. Exhibition praxis has attuned itself to the Zeitgeist and inevitable relies on media efficacy, not least in order to be able to survive financially. Elaborate exhibition scenographies with audience appeal are thus inevitably closely linked to their financial and media usability and exploitation. In this domain the application of new media is significant, though one must first analyse whether they mainly serve the emotional experience or also take on informative or practical demonstrative functions. This development is reason enough to view the use of electronic media in exhibitions and museums with scepticism.

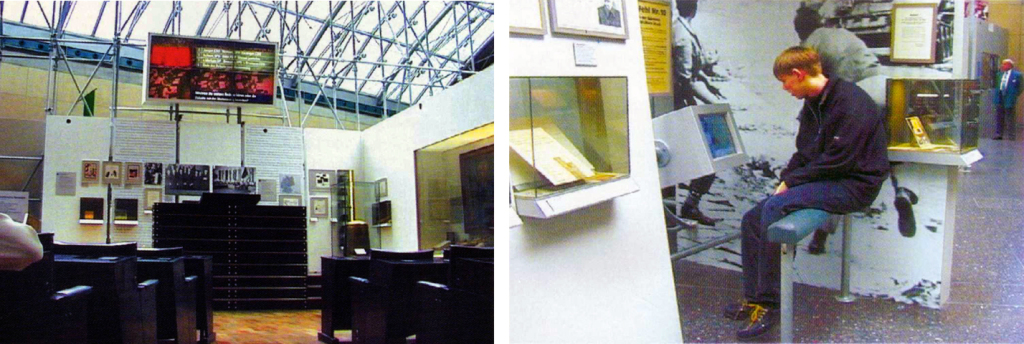

On the other hand, there are ever more positive, conceptually well-thought-out examples, planned for the long term. Museums such as Haus der Geschichte in Bonn, the small Aquarius Wassermuseum in Mülheim an der Ruhr or the internationally renowned science and technology museum Cité des Sciences/La Villette in Paris have all—as diverse as they are—trodden another path, away from event culture, without losing the character of being an experience that engages the visitor. What they have in common is the scenic integration of audiovisual communication as an integral part of knowledge mediation and their special design. The media take on very varied duties in these museums: they complement, for example, exhibits with additional information on their content, praxis or related history; they explain experimental conditions or simulate processes that can barely be demonstrated on exhibited objects. They can also take on tasks that are striking and animate the visitor as part of the exhibition scenography or become a part of a contemporary exhibition architecture.

Other museums such as the Getty Foundation, Los Angeles, or the Louvre, Paris, follow other media strategies. They cultivate, due to their self-images, what one could call a rather classical presentation style: the exhibit is the focus, the staging takes place between the art work, as main actor, and the museum space, as the stage. The advantage is that the architecture of both museums offers ample scenographic qualities for this. This presentation style is also certainly expected, in the case of the Louvre, by a rather conservative audience. In the Getty Foundation more focus is placed on the didactic line.

However, what both institutions have in common, alongside the classical line taken, is that they very successfully present interactive media such as CD-ROMs, the World Wide Web and video, parallel to the museum work, creating effective public relations and a public community. The Getty Foundation is also characterised here by being more didactic, while the Louvre concentrates on effect and international publicity. The Louvre has long since burst through and beyond its walls with its most remarkable productions: a virtual twin with additional related duties already exists since the end of the 1990ies. The Louvre CD-ROM of this time, for example, was one of the top-selling CD-ROMs in the world. This strategy of parallel media work—on one hand the internal media communication and on the other public relations, a significant part of which is based on electronic media—will surely be of growing importance for future exhibition or museum concepts, in particular with regards to digital databanks (which provide all the necessary data for archiving and cataloguing), internal audiovisual presentation and Internet presence.

Media contextualise exhibits – torn from their historical, local and sociocultural settings – make sense where the viewer has limited possibilities for interpretation or reconstruction. The discussion around a competitive restriction of the original or the exhibit through the apparent attractiveness of technological means of communication therefore still seems to me to be given too much weight.

The impairing of the aura, the insufficient concentration on the uniqueness of the object, are often arguments in the dispute over media that accompany exhibitions. But which aura surrounded and impressed the people of antiquity when they walked through the gates of Thebes? What is the aura of an object torn from its sacral context, whose ritual power we cannot even come close to understanding today? Does the aura transform through the viewers and their system of references? Does the aura feed on the demands of museal values?

There is nothing—with the exclusion of some works of art—more foreign and artificial for an exhibit than a museum or an artificially created exhibition space.

These are already staged situations beyond original scenarios and their contexts of meaning. The aura is not the original aura and the original, apart from its material appearance, is no longer that which it once was. Its meaning and appreciation now lies in the form of presentation and the re- or new-interpretation this results in. As such the object is subjected to perpetual change.

Even all attempts to create the most neutral environment possible that does not engulf the object at first glance must fail. There is also deception in the understatement of whitewashed walls, minimal labelling, a neutral protective display case and an abstinence from media: the scenographic moment remains. For what emphasises the object—torn from all contextuality—more than a display case in front of white walls?

Interactive dramaturgies: Learning from the model

What does this now mean for the education of young designers and artists who discover an interest in exhibition and museum design? My experience is that only a small number of students who have chosen to study design or art show any curiosity at first. Exhibitions are primarily occasions to show their own work in a positive light.

The fact that exhibition and museum design is extremely complex aggravates this situation. The remit ranges from interior and stage architecture, scenography and graphics to linear and interactive audiovisual media. In contrast to the mediation of the theoretical foundations of this theme, such a multi-layered approach can hardly be combined in terms of art and design. As such, education is about, on one hand, the question of suitable access, an orientation that satisfies the personal and creative interests and tendencies of young designers and artists and on the other hand, a focus that allows a targeted approach.

As the name already suggests, the creative and theoretical engagement with new media is the educational focus at the Academy of Media Arts Cologne. This also derives from the conviction that questioning, changing and making technology socially acceptable or adaptable only becomes possible through cultural appropriation. In this context I have developed a first study module on the theme of “Interactive and inter-media dramaturgies in museum and exhibition design.” The approach corresponds, on one hand, to the general objective of the academy to make media communication and new technologies the focus of artistic-creative work and on the other hand results in a concentration on a very specific aspect of exhibition design, namely the linking of scenography and new media in various thematic contexts and demands.

The field of exhibition scenography is nigh on ideal for this primarily media-related sphere. It is derived from the stage as the location of performance and integrates structural features that are comparable to a dramaturgy. “Scenography” and “setting the scene” are already suitable media-related models. I have expanded this approach with the concept of “interactive” or “inter-media dramaturgy,” in order to describe structural, but especially also cross-media features, that also take communicative aspects into consideration. This is an ideal connection for students who are mainly concerned with new and, as a rule, interactive media. At the same time, some very specific questions for young designers can be derived from this association:

– Does changing media behaviour, which can be increasingly observed among the younger generation, also require new exhibition concepts? – Are there structures in exhibition design that are comparable to the rules of interactive media? – Are there design potentials that reach beyond the use of new media as accompanying information programmes and open up new scope for creativity?

Large events such as the EXPO 2000, exhibition events like the “Sieben Hügel” exhibition in Berlin and lavish media art exhibitions such as “Vision Ruhr” have contributed to increasingly directing attention back to the theme of exhibitions and museums in the year 2000. These circumstances were also favourable for the planned purposes of offering exhibition design or exhibition scenography as a practical course of study.

First of all, excursions were taken with interested students to Haus der Geschichte in Bonn; Aquarius, Wassermuseum, Mülheim an der Ruhr; Museum für Angewandte Kunst and the Filmmuseum in Frankfurt; the “Vision Ruhr” exhibition in the Zeche Zollern in Dortmund; and to EXPO 2000, Hanover, with regard to the aspects of “first on-site experiences” and “stock taking.” In all of the museums, as well as at the EXPO, we were given outstanding introductions. The assignment for the students was to record the most important impressions in photographs and videos.

The creative criteria of the respective presentation were then documented by means of a catalogue of criteria we had developed together, which served as a first point of orientation. These criteria encompassed the public appearance including the preparation of information material and, where applicable, the Internet presence. Furthermore, the preparation of information internal to the exhibition in terms of content and design, that is all of the signage and other written information and labelling, visual and audiovisual materials such as graphics, photos, slide and video projections, sound installations and PC-based interactive programmes including CD-ROMs. Scenographic situations and dramaturgic aspects were illuminated, beyond the level of media presentation, for example the design of presentation in terms of the scenographic and staged areas, dramaturgic qualities, target-group specific areas and unusual, rather surprising forms of presentation that open up new ways of viewing.

Coming closer to the theme in terms of media-related and especially dramaturgic perspectives then led to the development of various models, which were checked for their transferability to exhibition and museum design. This touched on, among others, themes such as storytelling and narration, linearity and non-linearity, the change in dramaturgic concepts in exhibitions under the influence of interactive media, possible effects of virtually accessible contents and their computer-based presentation, for example in the form of installations, on scenographic design.

Cinematic narration: Elements of a classic dramaturgy

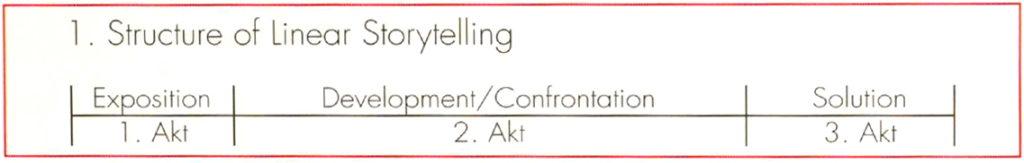

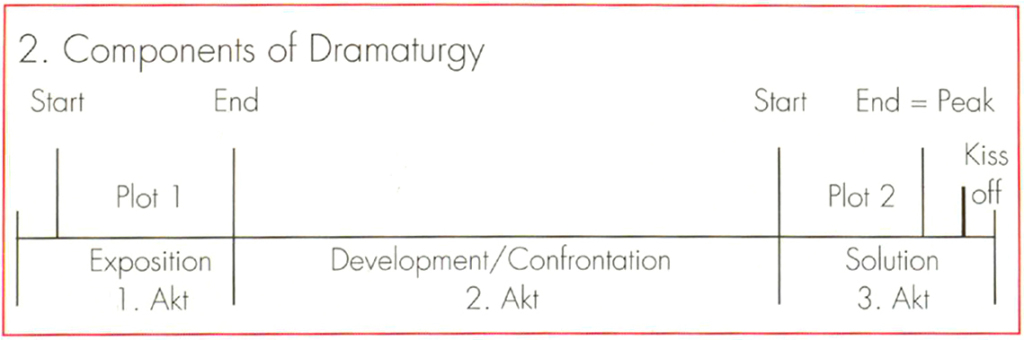

Media and especially dramaturgic strategies for exhibitions and museums can be derived from the most varied of fields: from literature, theatre, film, architecture, art and new media. Prerequisite is that these models are based on an expanded concept of dramaturgy.The dramaturgic structure of a linear medium such as that of the theatre or of film can be depicted in a simplified way as a linear organisation of episodes or events that build up to a conflict, which is then solved towards the end of the story.

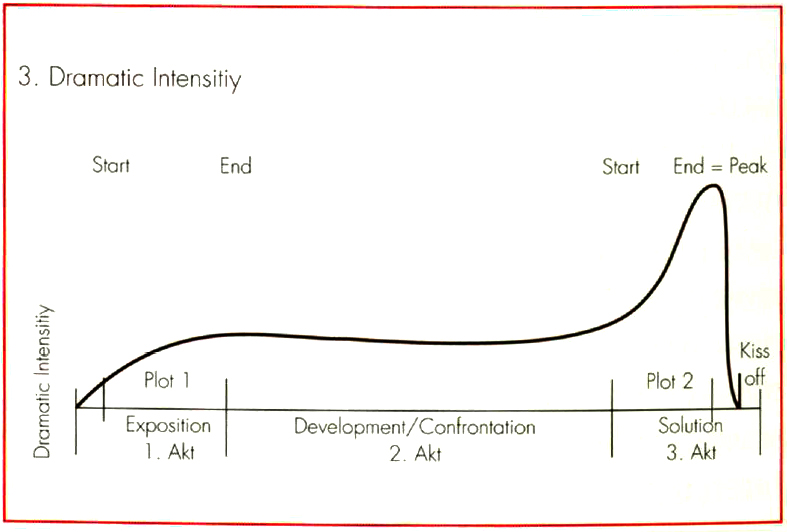

These graphs from Peter Hant’s publication Das Drehbuch visually illustrate a traditional system of narrative rules, which were first formulated in antiquity and still underlie, in a more or less modified form, narrative cinema for example—also Hollywood film. The exposition serves as the introduction of the main characters and establishes the plot. The development of the story up until the confrontation follows in the main section. The third section serves as the solution and leads to the resolution of the story. The classical play or conventional film are generally based on this three-act model.There are, in this temporally organised structure, other elements that are important for the narrative, the terminology of which is taken from scriptwriting: the hook, the plot and the crisis or intensification of the conflict as the moment of highest tension.

The “hook” is placed relatively early on in a story. It is the hook on which the attention of the audience is caught. This can happen through a sudden event or the introduction of an unexpected person. The audience is psychologically drawn into the action, curiosity is aroused. As such, the hook is one of the most important psychological communication features of classical dramaturgy. The “plot” follows the hook. Plot 1 is built up in the first act and, as a rule, leads over into the second act. After the beginnings of the story have been introduced, the plot develops a twist in what is accepted as having happened thus far. This is often an unforeseeable event that is extremely unsettling or confusing for the protagonist. This is where the actual story begins, which intensifies up until the confrontation. Plot 2, a further unforeseeable event, gives the story another lasting, completely surprising twist and leads to the inevitably dramatic climax. This plot is at the end of the second act and chiefly determines the third act, followed by the resolution of the conflict.

From this sequence of events, a growing dramaturgical intensity can be read, which serves to captivate the audience in the narrative over a fixed period. Dramaturgy aims to create an effect. Dramaturgy is a system of communicative and perception-psychological strategies. Complex stories have additional sub-plots, which introduce new people and other situations. These include memories, so flashbacks, or the anticipation of future events, and also dream situations and parallel plots. These are the most common narrative strands or sub-plots.

The media modification of time and space: dissolution of chronology

It is already clear from these statements that linear stories contain non-linear elements. Acts, sub-plots, montage, and cinematographic time disrupt the linearity. However, what happens is still presented in chronological order. This also goes for the representation of the cinematic space, whose spatial linearity is partially disrupted, but which can ultimately only open up along a temporal axis.

The interruption of chronology represents the really significant jump to the development of an interactive dramaturgy and offers up numerous points of contact for the scenographic design for exhibitions. The work of the museum designer is similar to that of a designer of interactive media. It ranges from the specification of chronological processes or events to individually determinable voyages of discovery for the visitor, from controlled paths of learning to the open structure of an explorative environment. The individual availability of time, a non-linear exploration of the space as well as the engagement with diverse exhibits, which are artificially condensed into museal time and spatiality like snippets from various epochs, cultures and geographic contexts, are all characteristics that are also particular to interactive programmes.

Even more examples that produce structural similarities between traditional narrative forms and new media can be listed in this context. The Finnish actor and media artist Mika Tuomola draws parallels, for example, between dramaturgic characteristics in commedia dell’arte and the dramatisation of virtual communities through avatars in his article Drama in the Digital Domain. Commedia dell’arte is distinguished, on one hand, by a certain openness, which, as Tuomola says, offers an ideal role model for narrative degrees of freedom and narrative branching and as such allows the actor or avatar a corresponding freedom of action. On the other hand the dramaturgic framework contributes to a necessary orientation and a thematic continuation of the action. There are also thought models here—beyond Tuomola’s statements—that are thoroughly suitable, for certain topics, as conceptual approaches in the exhibition field.

Television behaviour:

Farewell to classical viewing habits and dramaturgic rules

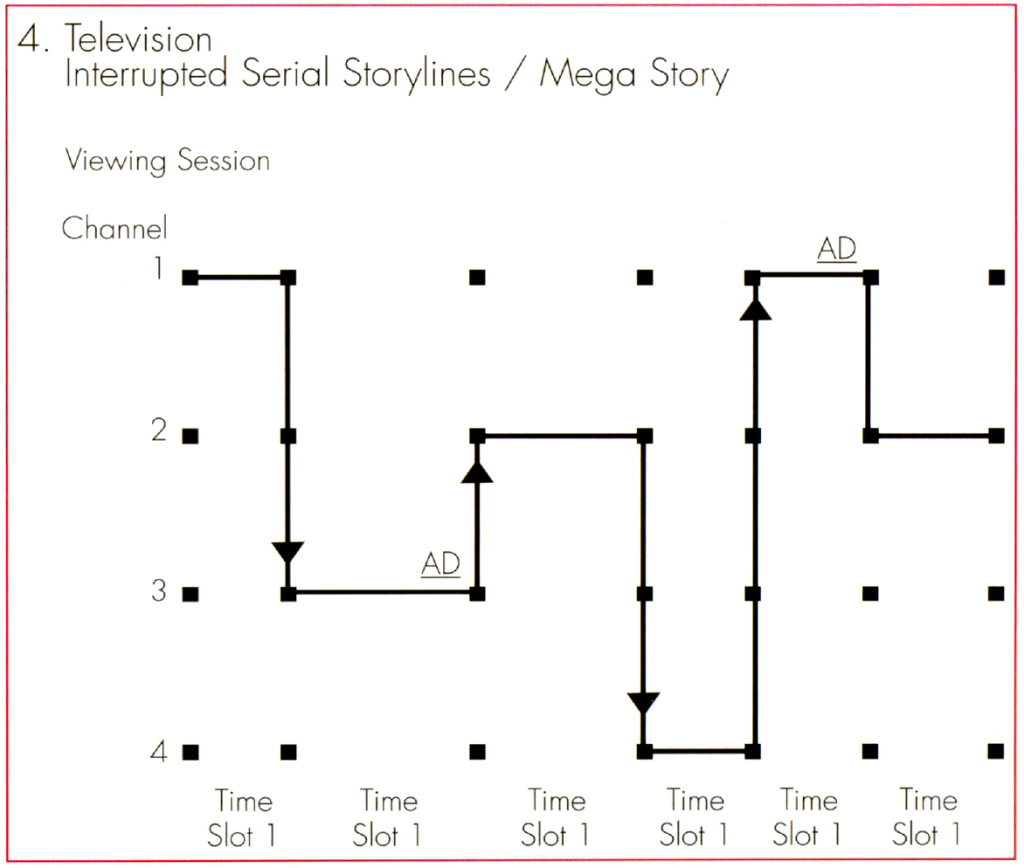

The large-scale introduction of the infrared television remote control changed television in an almost revolutionary way. Television is no longer a single broadcaster, but rather a system of numerous broadcasters and this will continue into the future with cross-media high-performance broadband networks—i.e. interactive networks. In the last ten years television has already bid farewell to classical dramaturgy. This doesn’t necessarily refer to individual programmes, but rather the over-all appearance of the medium or the total system. Television is the medium of non-chronological communication, links and mega-stories. Television has already changed our perception habits and has developed its own conventions beyond those of film, theatre and literature. For example, stories are continually interrupted by blocks of adverts or actively by the channel-hopping viewer. Additionally, passionate television viewers only rarely concern themselves with one programme, but are more inclined to parallel viewing. This has logically led to the development of television-specific formats, altered dramaturgies and contents.

Diagram 4 deals with a viewer’s tune-in phases. It shows which channels were selected and left or interrupted by blocks of advertising (AD). The viewer navigates through four channels and temporarily comes back to previously selected programmes over six units of time. What is interesting is that channel-hopping clearly does not lead to considerably losing touch with previously selected programmes or make them no longer comprehensible. In fact, standardised contents and dramaturgies resolve this contradiction, the over-all context remains understandable and can be consumed as a kind of mega-story. The smallest units already enable an understanding of the whole. Genres therefore follow very rigid rules: sports programmes, soaps and talk shows can be deciphered and understood in parallel.

It is also interesting to check to what extent both coincidental and interest-led hopping between topic areas, so what we can clearly call changed communication behaviour, is relevant for exhibition concepts. What becomes striking is that there is a growing willingness on the part of viewers or also visitors to link contents associatively with one another and to accept or expect considerably more complex perception structures. What happens when the visitor orientates themselves according to these patterns? Can an exhibition dramaturgy incorporate these patterns of behaviour in a meaningful way? Does scenography predetermine patterns of behaviour? Or do the communication habits of the visitor predetermine scenographic guidelines?

Media behaviour:

Interactivity as a component of dramaturgic and scenographic designs

Interactive media such as the World Wide Web, the CD-ROM or interactive television are based on individual choices and perception preferences and on individual units of time. This applies equally to exhibitions: they are basically interactive environments that are accessible in similar ways. The visitor behaves actively. He decides on the focus of interest, he determines individually how long to stay, he can leave predefined sequences and—like a channel-hopping pattern—navigate through the exhibition.The group experience also shows parallels between some interactive media and exhibition situations: exhibitions are classical “multi-user” platforms.

Interesting in this respect is the recourse to dramaturgic rules and their transferability to interactive situations, whether these be purely media-based or, as in the exhibition context, spatially related. Well thought through exhibition strategies always include elements of a classical dramaturgy too: they make use of a “hook” in order to capture the curiosity of the visitor, as this is where a continued participation in what is happening is already decided. They develop surprising moments parallel to the plot in order to capture the attention. They offer sub-plots or discovery paths, in order to escape chronological one-dimensionality. They culminate in climaxes, also in gratification for the effort afforded and should, preferable, end in an interesting moment of resolution. In principle, these are communicative strategies that are implemented through dramaturgic rules.

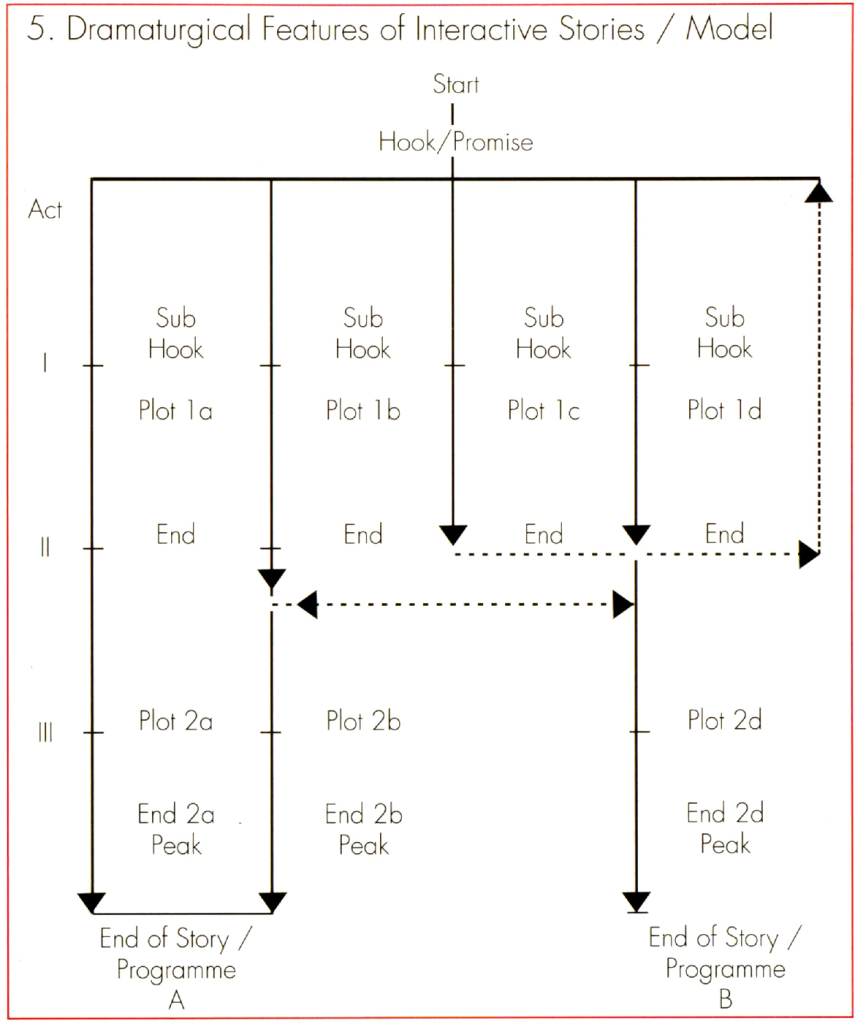

Diagram 5 represents a possible, greatly simplified model of an interactive programme, which could also be transferred to exhibition situations. The main theme is divided into four sub-themes, which correspond with one another on various levels. Two methods of resolution or approaches (programme A and B), which can be followed on various paths, are offered. The viewer/visitor also has, alongside linear or chronological paths, the possibility to proceed block for block or island for island and to select various content focuses from amongst the sub-themes. Every sub-theme or path contains dramaturgic elements, which can be classified as communicative strategies. At the same time, they determine the framework of the creative implementations or scenographic executions. These features of an interactive programme can, in my view, be projected onto a creative exhibition concept without any problems.

The space as metaphor: Navigation as dramaturgic element

Interactive media and exhibition design come even closer to the structural organisation of information. Most interactive products deviate from the linear stringing together of their different theme areas. They allow the viewer to explore thematic fields according to various spatial patterns. The space thus becomes a metaphor of interactive navigation and orientation strategies.

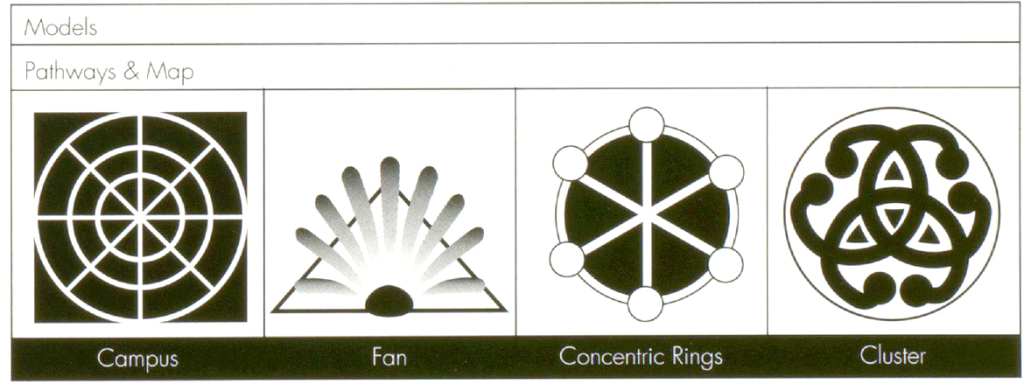

Michael Utvich, author of interactive media programmes, has designed virtual communication spaces for various types of navigation, derived from architectural models (diagram 6). Navigation spaces can consequently take on the form of maps or plans, be presented as campus or fan, appear as concentric rings or clusters and so on.

These spatial models accommodate complex story and narrative worlds. In addition they contain two completely essential functions: they serve, on one hand, as orientation for the viewer or the visitor in exhibitions and on the other, organise or structure the content. These space models thus contain essential guidelines for the author and exhibition designer, as well as guiding the user. They are the framework of the exhibition script, which codifies both the demands made of the design and visitor management.

As in most spatial orientation models, rules, a kind of guidance system, must also be created and observed here. Interactive programmes are based on rules that have to be created by the author and learned by the user. For example, that one can only reach level C if levels A and B are passed through, thus also a consistently chronological moment. Certain rules of interactive programmes have already become part of a conventionalised symbolic and behavioural system, for example instructions that are found in navigation areas or navigation bars, pop-up menus, changes in cursor, image and sound etc.

A comparable situation is found in the exhibition context. The exhibition designer determines patterns of hierarchies or also levels and paths on equal footing. He creates rules on progressing and procedures, defines linking points and spaces for free association.

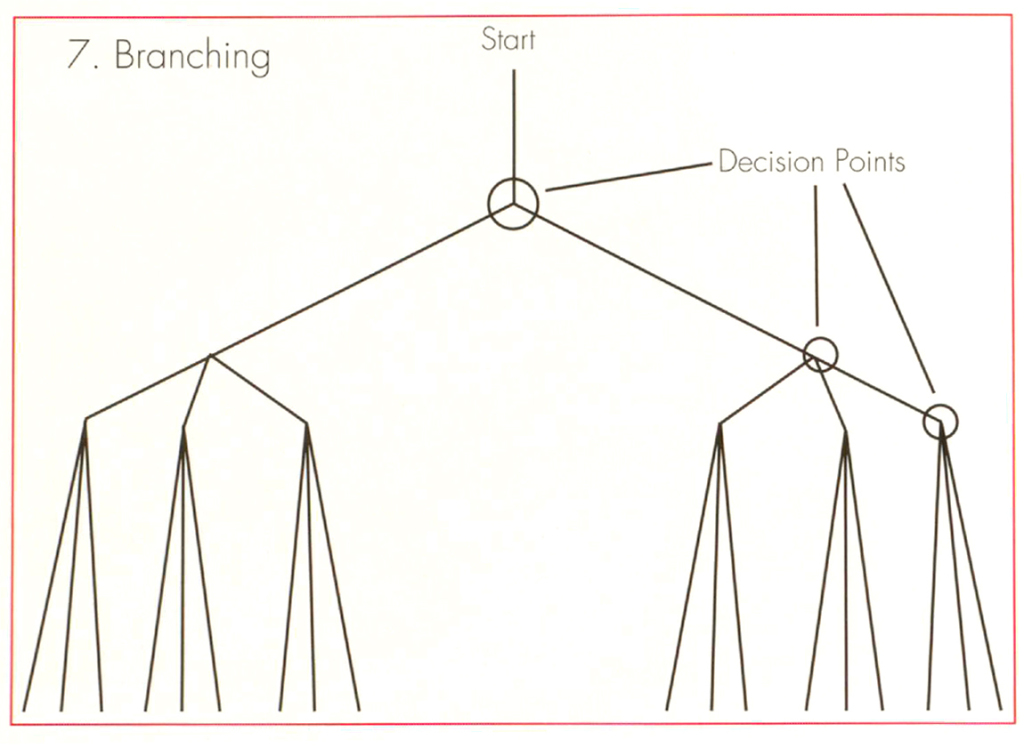

One of the most common forms for structuring interactive contents thus far is branching. Here the viewer makes his decision as to how he wishes to pursue the story further at the forks. This simplified model is taken as a basis for, among others, the first attempts at interactive film as well as the first interactive text and image based network systems, videotex or Bildschirmtext systems, but is, without further ado, also transferable to the organisation of exhibitions. The decision points are located at thematic or spatial transitions. Instead of different ends, junctions or bundles are also possible here, which lead towards a common goal or a common exit.

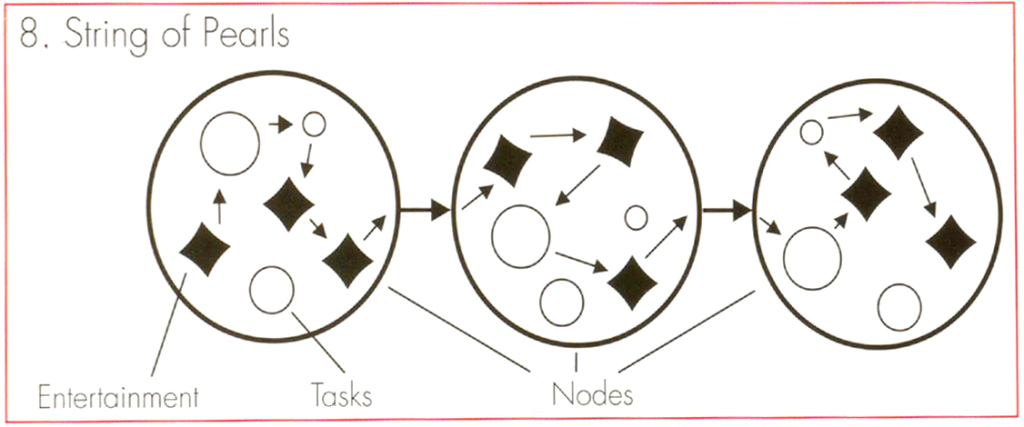

Another method is the string of pearls, which can also be connected with various spatial strategies. The viewer, who enters a node or a pearl, can only make the transition to the next node when he has completed certain tasks or has become acquainted with the content in this space.

This model, which has been further developed as an intelligent dynamic model for the games branch by Jobst von Heintze, also contains interesting approaches for learning programmes and the field of edutainment. Transition between the nodes is determined by the author, but what is exciting is that the viewer or visitor can act relatively freely and playfully within the boundaries of the respective node. Offerings are developed to this end that, along with the solving of a task, hold entertaining elements in store, so-called cookies. This solution promises to be met with high acceptance, especially in the educational field. Here again it would seem obvious to make use of this approach for exhibition situations.

Complex exhibition scenarios, which work with numerous levels of information, can build on comparable models. Predetermined, defined paths are set as learning paths, while entertaining and playful explorative elements enable target-group specific approaches, which surely contributes to increased visitor acceptance. Here, the navigation in the exhibition area within the nodes becomes an essential part of a dramaturgic exhibition concept.

Hybrid worlds: Towards a dramaturgy of virtual and real spaces

All these forms of interactive design and interactive scenarios offer, from my point of view, models that can also be adopted as dramaturgical patterns in exhibition scenography. The handling of new media thus offers interesting illustrative models, giving reason to address the exhibition design of the future from different angles, for example those of media perception and behaviour.

Scenographic or dramaturgic parallels are to be found, among others, between exhibition and networked systems. This was already apparent in historical precursors such as the Wunderkammer. The order of the objects in the Wunderkammer (curiosity chamber) represented a self-contained network but simultaneously a closed system, whose referential universe was initially exhausted in the reference system of the collector. Each part corresponded with the other and at the same time referred to an external world, which offered links to complex interrelationships for the collector. So networked and associative designation is neither new nor based on technology.

What is new, however, is that systems are developing that, on one hand, reach out beyond the spatial discourse and become generally accessible, and on the other, set the individual standpoint of the collector of the past against a collective. Exhibitions such as “Sieben Hügel” in Berlin in the summer of 2000 have spun cultural, scientific and artistic set pieces, with great effort, into a network of associations and interpretations. This extended as far as scenographic design, which itself became a citation. Event based exhibitions like this one, or on a considerably larger and more costly scale the EXPO 2000, are very close to the Internet experience: the visitor “surfs” through what is on offer, follows links and creates their own paths. Appropriation processes are extremely individualised and pretty much rely on associative links.

An engagement with virtual models, especially virtual spaces, must also lead to new styles of thinking and imagining, which could find their precipitation in future exhibition design. This would be a matter of dramaturgies of virtual and real spaces as well as questions of their reciprocal permeation. However, the fusion of virtual and real aspects in a networked system places completely new demands on spatial scenography and dramaturgy.

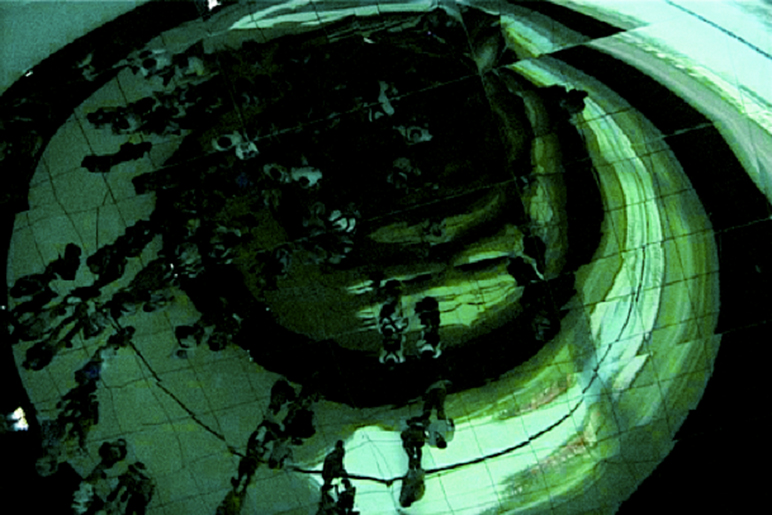

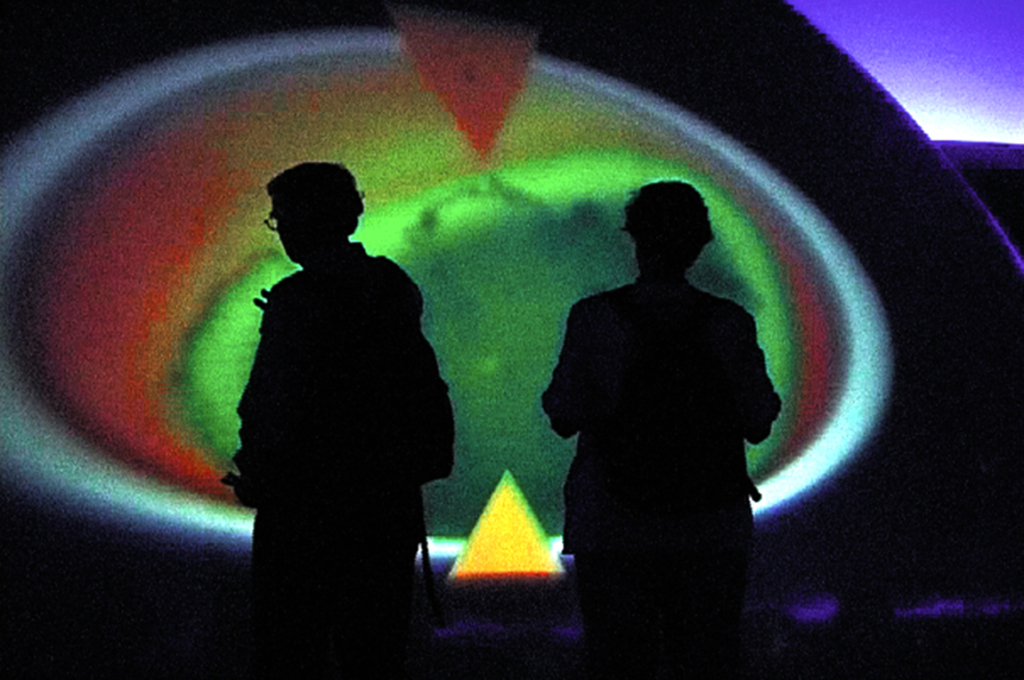

The architect, musician and exhibition designer Ranjit Makkuni has dealt with the transitions between virtual and real environments and the possibilities of integrating them meaningfully in exhibition concepts for many years. His exhibition project Banaras – The Crossing, which he realised with the XEROX Center in Palo Alto, is one of many examples that follow this approach. Banaras thematises the sacred Hindu site on the Ganges, where the large Eastern world philosophies originated. Banaras is a place of pilgrimage, a place of death and transformation and simultaneously the place of a living Hindu philosophy and religiosity with numerous schools. It is the place that marks the transition between life and death, the material and the spiritual. Materiality, spirituality and virtuality are also the themes that concern Makkuni.

The spatial organisation of his exhibition, which is currently in preparation (in 2000), is borrowed from the model of a multi-layered, concentric interactive programme. The visitor advances in circles into ever-deeper regions of knowledge mediation. So-called “intelligent objects” impart information about their cultural context or their functionality and the meaning they hold beyond their mere appearance. As a “multi-level exhibit,” live connections to the sacred place of origin on the Ganges are to be created via the Internet, in addition to the respective exhibition location. Participation in rituals and lessons led by philosophers who work there are planned, among other things. This dynamic permeation of scenographic elements at the transitions between reality and virtuality in the networked system points to ways that should certainly be analysed more closely and re-formulated for future exhibition design.

The world as a network and open system:

multi-tasking and future exhibition dramaturgy strategies

How much communication habits influence strategies of exhibition design will become apparent over the coming years, with a generation of visitors socialised through media. Mary Modahl, vice president of the Forrester Research Group, which is concerned with the analysis of altered media and communication habits, gives the following key points on this (2000):

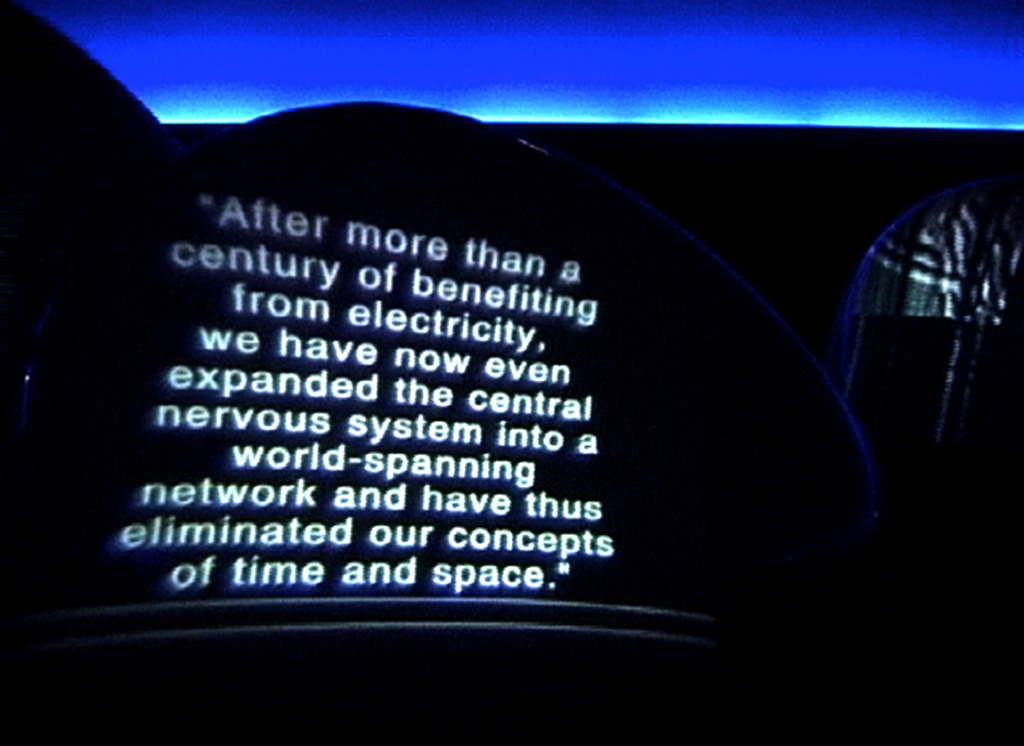

Children and young people grow up with a multitude of media at their disposal nowadays. Radio, television, magazines, newspapers, telephone and access to the Internet are used as a comprehensive communication experience, as mixed-media platforms. Communication is played out simultaneously on several levels. One can also speak of multi-level or multi-tasking behaviour here: the teenager magazine is read during the television show, homework done on the PC is interrupted by chats and surfing, so at the junction between “desk” and virtual environments.

Networked children also learn very early on that they can share contents with others. It is not rare for children in the USA (2000) to keep in touch with 100 or more people, also beyond national borders, and experience that, for example, advice and support can be received from many people linked to one another—a virtual peer group—no longer just from one person equipped with a certain authority. They also learn that products are “open,” i.e. programmable and changeable, and stasis in no longer relevant. Electronic products can be expanded through “downloading.” The generation currently under twenty years of age is growing up with computers being very much a matter of course. Young people in the USA already spend approximately 30 percent of the money at their disposal on online services.

It can be assumed that media will not only change communication habits, but vice versa, changing communication habits will also change media.This means: the permeation of real and virtual presences will hardly be an issue here, rather part of a new reality, which will very quickly catch up with the ww

How will exhibitions that are aimed at this target group or which are produced by this generation itself, be designed, scenographed and dramatised in the future? Which function does the physical space retain? Are hybrid situations, i.e. the linking of virtual presences with partially physical location, the exhibition concepts of tomorrow? Or will exhibitions and museums become completely virtualised and their physical experience attributed little relevance? Which influence does networked thinking, a perception shaped by multimedia and the ubiquitous availability of digitalised information through portable communication media, have on future concepts of exhibition design? I think that a wide field of approaches relevant to behaviour and communication is opening up here, which will yield and must yield completely new presentation models in connection with experimental exhibition designs.

Literature

Eisenbeis, Manfred, and Heide Hagebölling, eds. Synthesis – die visuellen Künste in der elektronischen Kultur/Visual Arts in the Electronic Culture. International Unesco Symposium. Hochschule für Gestaltung Offenbach, 1989.Eisenbeis, Manfred, and Heide Hagebölling (in collaboration with Achim Lipp and Philipp Heidkamp). Infosphären – Information als Orientierung, Animation und Erlebnis. Space and media concept of the visitor information system of the EXPO 2000 in Hanover. Cologne, 1998.Hagebölling, Heide. Zur medialen Vermittlung von Kunst und Kultur. Munich: Visodata, 1984.Hagebölling, Heide. “Interaktive Dramaturgien – veränderte Kommunikations- und Erzählformen.” In Digital Storytelling. Tagungsband, edited by Ulrike Spierling. Darmstadt: Fraunhofer IRB Verlag, 2000.Hagebölling, Heide, ed. Interactive Dramaturgies: New Approaches in Multimedia Content and Design. Heidelberg/New York: Springer, 2004.Hant, Peter. Das Drehbuch. Praktische Filmdramatugie. Waldeck: Felicitas Hübner Verlag, 1992.Kaifa, Yasmin and Mitchel Resnick, eds. Constructionism in Practice. Designing, Thinking and Learning in a Digital World. Mahwab NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc. Publ., 1996.Laurel, Brenda. Computers as Theatre. New York/Tokyo/Paris: Addison-Wesley, 1993.Lunenfeld, Peter, ed. The Digital Dialectic. New Essays on New Media. Cambridge Mass./London UK: The MIT Press, 1999.Makkuni, Ranjit. “The Crossing: Living, Dying and Transformation in Banaras. A Multicultural Learning Project.” In Interactive Dramaturgies, edited by Heide Hagebölling. Heidelberg/New York: Springer, 2004.Tuomola, Mika. “Computer as Social Contexualizer and Ideatre – Towards the Promising Future of Avatar Worlds.” In éc/artS#1, spécial:textualités & nouvelles technologies, edited by Éric Sadin. Paris: Dif’Pop, 2000.Utvich, Michael. “Write a Story like a Building” and “The Circular Page.” In Interactive Dramaturgies, edited by Heide Hagebölling. Heidelberg/New York: Springer, 2004.von Heintze, Jobst. “Emergent Stories – eine neue Herangehensweise zum Erleben und zum Authoring Interaktiver Geschichten.” In Digital Storytelling. Tagungsband, edited by Ulrike Spierling. Darmstadt: Fraunhofer IRB Verlag, 2000.