Trust and Confidence in the Artistic Process. – An Insight into the Creative Lab

Heide Hagebölling-Eisenbeis

Vertrauen und künstlerischer Prozess – Einblick in das Kreativlabor

Trust, Confidence and the Creative Process – Inspecting the Creative Lab

In Wilharm, Bohn: Inszenierung und Vertrauen / Staging, Trust and Confidence

Ed. Transcript 2010

All rights of his article by the author

When Heiner Wilharm and Ralf Bohn offered me the chance to take part in the 2nd Scenographers’ Symposium in 2009, under the heading “staging trust and confidence,” I was slightly puzzled. Firstly I was faced with the question of how “trust and confidence” could be staged, and secondly I wasn’t at all familiar with the kind of relationship staging and trust have to one another. The rhetoric of ubiquitous trust-forming activity came to mind at first: every day we are bombarded en masse, via the media, with stagings that unmistakably solicit trust. Neither politics, economy nor culture is exempt from this. The staging of trust—as a marketing tool and economic calculation.

The conjunctional connection between staging and trust, on the other hand, leaves scope, beyond this rhetorical expediency, to consider the quality and necessity of trust, especially in the area of artistic work. The question posed is how trust anchors itself as a qualitative—and elusive empirical—feature in the creative process, what influence trust has on collective decisions and to what extent trust can compensate for a lack of facts, reliable predictions or for conditions that can not be clearly defined. So anything that can be foreseen through a positive interpersonal and collective anticipation of future expectations and goals and as such contributes considerably to the ability to act.

I have been involved with expanded video, the electronic moving image in space-related contexts and interactive installations, as well as with questions of interactive non-linear dramaturgies, for more than 20 years. I have also become increasingly interested in media scenography, which comprises all of these approaches while simultaneously opening up a broad area of trans-disciplinary work, cooperation that involves, depending on the project, the most varied of artistic practices.

The participants in these fields of work, also practiced in my classes, are young artists, filmmakers and designers from the most diverse of backgrounds and nationalities, as well as dancers and choreographers, musicians, theatre directors as well as cooperative partners from the worlds of culture and business, according to the respective project. These heterogeneous groupings develop artistic themes together, are open to group processes, are prepared to risk failure and explore unknown territories for the goal of collective artistic success. These groups are not organised pyramidally, they do not function as classic hierarchies and likewise no contractual bonds or provisions are created. Cooperation with external partners, should third-party funds be in play, is arranged in simple written agreements. Otherwise it is verbal agreement and the collective intention that counts. These are ventures without a safety net. Trust both on an interpersonal level as well as in the collective cause—it has become apparent to me—is the actual glue that holds these groups of artists, as well as their visions, together. Artistic production—as long as it is not commissioned art or functioning within the framework of the cultural industry—cannot exist without trust and confidence, as it initially stands outside the usual chains of valuation and binding sets of rules.

This article therefore concentrates on the dimension of trust in the artistic creative process, i.e., on the roots of creation. The dimension of trust can likewise be transferred to the work itself, to its intent, its aesthetic realisation, its reception and its effect. As such, trust runs through the whole process of communicative and artistic action and understanding and is certainly also highly significant in determining the acceptance or rejection of a work of art.

Seen etymologically, the word “trust” can be traced back to the Old Norse word “traustr” meaning “strong” but is surely also related to “true,” and thus addresses all of the characteristics that undoubtably constitute an important tenor of artistic work. In the socialisation of children we speak of “basic trust,” the relationship with the parent that offers the child the necessary reassurance and safety in its encounter with the unknown and undiscovered world. It is still an unmotivated, almost blind, trust that only becomes differentiated later on, through the formation of a personality and cognitive faculties as the basis of social behaviour.

How is trust formed? Niklas Luhmann addresses the learning of trust in his book Trust, which deals primarily with the reduction of societal complexity in highly differentiated social systems: new situations and new encounters present new questions of trust all the way through life. As such, trust is not static, not a condition, but rather it is constantly in flux, in comparison to past experiences. It is therefore founded on credibility, reliability, commitment and authenticity and is a sine qua non of all inter-human cooperation. Social relationships would be impossible without trust.

Media scenographies are the result of dynamic group-related work. It would seem of interest to me in this context to view the dynamics of creative working processes in the light of Luhmann’s claims on the function of trust.

To begin with, the observation that familiarity with the respective theme or discipline strengthens the group’s trust and opens up the discussion for new and untypical solutions is applicable. This is generally preceded by a period of getting to know one another, of testing expectations, attitudes and reactions, the creation of a common story. This stabilisation is prerequisite to the creation of trust, especially in hierarchically weak groupings. Fields with marked divisions of labour—which are to be found in the culture producing industries, for example filmmaking, but also to a certain extent in theatre or in orchestras—partially compensate for this effort through norms and fixed roles.

In general, the complexity in a non-hierarchical group of people on equal footing is much greater than in hierarchically structured groups. Concentration on the basics, right up until the collective result, therefore often involves long-term dialogues and processes of convergence. At the same time, however, there is also much greater freedom in terms of experimentation and alternative forms of activity. Trust—based on agreement—plays a serious role in this process, by reducing complexity. However, there is only absolute certainty once the result is presented to the public. This is what decides on positive or negative reception, success or failure. As such, risk is par for the course. One could also say, trust contains risk.

Artistic work actually transgresses, per se, the familiar—in the sense of that which has passed—in that it constantly creates new forms of expression, opens unfamiliar perspectives, admits frictions, forms irritations and sets the familiar against unexpected possibilities, in other words, by creating complexity. As such art, in all its forms, is aimed at the future, partly with an uncertain outcome. Trust is prerequisite, especially when there is such a degree of unpredictability.

“The past,” writes Niklas Luhmann “does not contain any ‘other possibilities’; complexity is reduced at the outset.” He continues: “But rather than just being an inference from the past, trust goes beyond the information it receives and risks defining the future. The complexity of the future world is reduced by the act of trust.”¹

¹Niklas Luhmann, Trust and Power: Two Works by Niklas Luhmann (Chichester: Wiley, 1979) 19–20. Trust in the broadest sense, including trust in ones own expectations, must be fundamental for creative work. Artistic work plays with manifold, mostly unconventional possibilities and as such contributes to a greater complexity of the perceived world, in experiencing, acting and recognising. Numerous concurrences with Luhmann’s claims are to be found here. Trust, as an opening and simultaneously regulating entity, is prerequisite for an artistic system that takes on the risk of new and modulated forms in order to provide alternatives that challenge the recourse to proven methods.

Trust takes on a comparable regulative function in the artistic work process, especially when several partners are involved: through the differentiation and reduction of what first appears to be unlimited freedom of choice, the artistic process now concentrates on a manageable number of collectively borne possibilities and occurrences, which then shift to the core of the collective artistic interest until the final outcome is reached. Experience—as a historical dimension—is the skeleton, the framework, but is overwritten by new ideas and solutions during development.

These processes happen almost naturally in everyday practice. Only rarely do they become the subject of closer consideration or reflection on group dynamics. The network of trust is widely spread: it stretches from internal group processes, which are especially addressed here, to cooperation partners and their support, right up to the recipients. Without trust from all sides, none of the works more closely examined in the following paragraphs would have been realised.

In recent years there have been, alongside individual projects and graduation pieces, an increasing number of group and cooperative projects in the areas of media staging and artistic installation at the department of Video / Interactive Media & Scenography. Historical influences from the Bauhausbühne and cybernetic light installations by, among others, Moholy-Nagy, crossovers from painting, film and music, as they were thematised, for example, by avant-garde film in the 1920s and 30s, currents in visual music and synaesthesia, influences from expanded cinema and the study of contemporary artists as well as new technologies form a wide network of orientation for artistic engagement.

The examples of work introduced here, created for public concert/music events as well as in the context of a company museum, should offer an overview of the wide range of creative approaches. What these projects have in common, among other things, is that they tread new, unfamiliar paths in production and presentation.

Scenographic works in the fields of theatre and dance—such as Henry Purcell’s semi-opera King Arthur from the year 1691, performed during the international Shakespeare Festival in Neuss in 2007² and first realisations for the San Francisco ballet, Minimal Move, to String Quartet No. 2, 3 and 5 by Phil Glass, first performed during the Kölner Philharmonie summer gala in 2010³—will soon be studied in more detail elsewhere.

²The semi-opera King Arthur by Henry Purcell, libretto by John Dryden, was performed in 2007 as part of the international Shakespeare Festival in the Globe in Neuss. The director Nora Bauer, in cooperation with Das Rheinische Landestheater, Capella Piccola and Metamorphosis Ensemble Cologne, was responsible for the script, direction and production. The scenography, which was mainly black and white, was based on motion art, sound design and the use of VJing programmes.

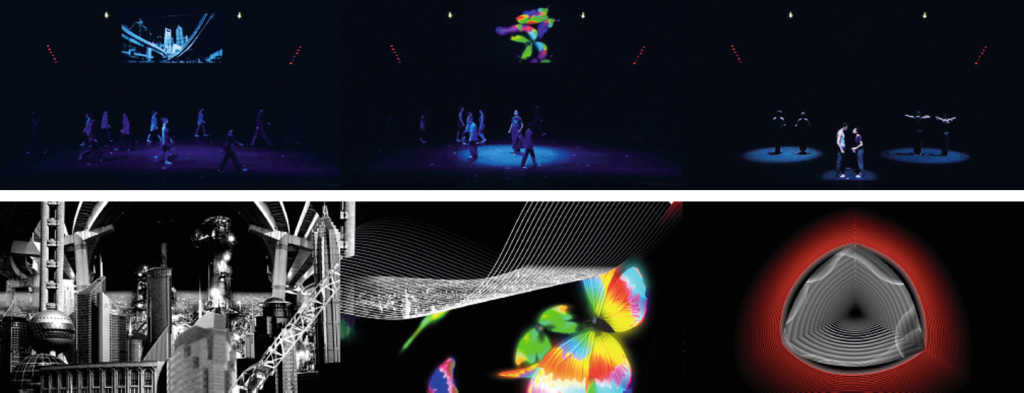

³Minimal Move (dance and media scenography) took place in the Kölner Philharmonie as part of their big summer gala on June 3, 2010. It was a collaboration between the “Media Scenography” faculty of the Academy of Media Arts Cologne, under the collective project management of Heide Hagebölling, the choreographer Mateo Klemmayer and dancers from the San Francisco Ballet. The participating artists were Kenta Nagakawa and Luis Negrón van Grieken.

1. PERCUSSIVE PLANET – CLASSIC VJING

Media scenography: visual music/motion art, VJing, video, light, live directing.⁴

In 2006 we were asked to design visual compositions for a concert, during the international Beethovenfest Bonn, by multi-percussionist Martin Grubinger, who was 22 years old at the time. Martin Grubinger’s Percussive Planet – Long Night of the Drummers developed into a 6-hour-long musical trip around the world with pieces by 35 composers including Aaron Copland, Iannis Xenakis, Steve Reich, Ástor Piazzolla, Leonard Bernstein, John Cage, Dmitri Shostakovich, Anders Koppel, Nikolai Kapustin, Toshimitsu Tanaka, Minoru Miki and Martin Grubinger. The performance took place in the T-Mobile Forum in Bonn, using what was the largest LED wall in Europe at the time. A project of such scale could only be realised by a professional team that could face the double challenges of avant-garde classical music and a tight deadline. We were fortunate enough to recruit the Cologne group Lichtfront – visuelle Musiker, founded, among others, by former students of the Academy of Media Art Cologne (KHM) postgraduate course, as well as the interior architect and media designer Frank Horlitz, who acted as artistic director.

Together with professional VJs and visual designers, who brought with them experience in film, motion art and interactive installations, a new format was developed: Classic VJing, which involved visual scores, composed in their appearance and rhythm for each different piece of music and rehearsed with the orchestra. One of the core elements of this musical marathon was the dramaturgical design of the evening as a whole: to begin with the sequence of the pieces, rhythm, complexity, phases of calm, climaxes, change and moods. The visual composition, as an additional sensual layer, could then pick up these impressions, to strengthen, weaken, or run against them, but also to add counterpoints, thus creating a meta-composition that respected the characteristics of both art forms and simultaneously combined them to create an expanded audiovisual experience.

A significant development was the distinctiveness of the collective live performance: the musical orchestra was now confronted with a motion art sextet, which played—analogous to the musicians—image-generating instruments. Not only did this audiovisual session develop a completely new quality of musical experience, it also had a dynamism and intensity that was able to carry the event, without a break, for several hours. This successful symbiosis of visual and audial art forms could only be borne on a foundation of collective trust.

From a scenographic perspective, this project also opened up new artistic approaches and demands: the scenographer became part of the public, artistic performance, moving from behind the scenes to centre stage, not only as a performer, but also as a dramaturge and author, acting in the environment they themselves designed and created.

⁴Percussive Planet was performed as part of the international Beethovenfest in Bonn in 2006. Initiated by the festival’s Director General Ilona Schmiel and Head of Artistic Management Tilman Schlömp, together with Heide Hagebölling of the KHM, a new form in the fusion of contemporary classical music and the art of the moving image was created. The group Lichtfront, represented in this project by Jörg Thommes, Svenja Kübler, Stephan Müller, Ingo Pelmer and André S. Gronewald, have performed at events all around Europe, as well as in Taiwan, Singapore, Manila and Las Vegas to name a few. Martin Grubinger is regarded as one of the best percussionist in the world and has performed extensively, including concerts in Lucerne, Cologne, Paris, Amsterdam, Vienna, Brussels, Stockholm, Athens and New York.

2. CHATTIN’ WITH CHET – THE CHET BAKER STORY

Media scenography: jazz clips/animations, narrative clips/motion art, VJing, video, light, live direction.⁵

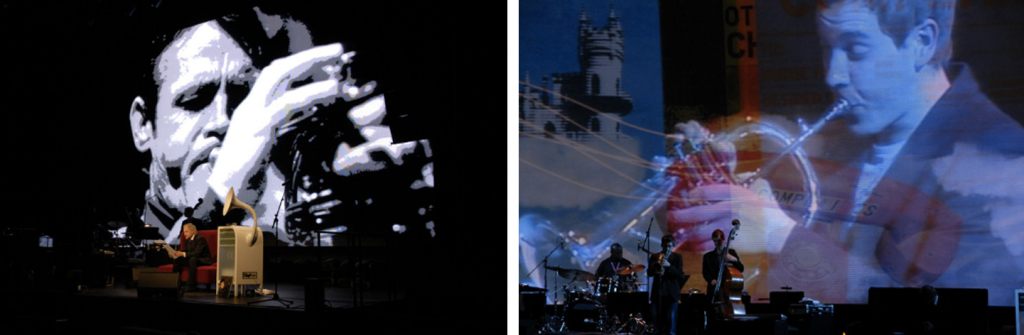

Through the experiences of the Percussive Planet performance, a second project, Chattin’ with Chet – the Chet Baker Story, was developed and performed in May 2008, also in the T-Mobile Forum in Bonn. This two-hour-long performance with Uwe Ochsenknecht, the jazz musicians Gerard Presencer, Allan Praskin, Julian Wasserfuhr and Presencer’s London jazz band, was made up of a reading about Chet Baker’s life and 12 of his most famous pieces. The remit was to create an audiovisual meta-concept, but the modalities—live performance by the visual artists or playback of pre-produced motion art—were left open. Chet Baker was carried out as a group project with students from the KHM’s “Media Scenography” faculty. Unlike Percussive Planet, there was no opportunity to rehearse with the jazz band. The binding elements for all those involved were the predetermined pieces, their sequence, the use of the narrator and the biographical text by the author Marcus A. Woelfle. As there were no up-to-date recordings of the Chet Baker pieces by the band, only historical recordings were available as orientation, which it could be assumed would be significantly different in tempo, accents, feeling, phrasing as well as improvisation. Gerard Presencer was known to us, for example through his recording of Cantaloop with Us3, as having a completely different musical approach. In addition it was to be expected that there would be encores, improvisations as well as differences in timing in the live concert situation, also depending on the reaction of the audience.

Methods had to be found quickly to deal with these unpredictable moments, which on the one hand allowed flexibility and reactivity, but on the other hand contained constants, so that a two-hour-long programme with congruous content could be presented. In addition this was to be realised without any dip in standards. In response, we developed a format between jazz video clips and music animation for the jazz performances, and miniature essays/narrative video clips for the reading, both prepared for looping functions, changes in tempo and rhythm, as well as a free choice in their sequence during the performance, as is the case in VJing. Videos of approximately two minutes length were produced for each piece of music and every passage of content, picking up all of the characteristics of the respective piece and text. As we had decided on a live performance with a combination of playback, VJing and live direction, including live camera, all of the visual elements could be looped at will, their tempo varied and order changed. These flexible parameters thus enabled an instantaneous adaptation to the characteristics of the musicians’ interpretation and the reading. At the technical level we decided on an A-B split via two high-performance laptops in high definition format, a back-up computer, a digibeta video camera and a vision mixer, which could handle all of these various formats live and feed them to the LED wall. All of the lighting direction and colour schemes were attuned to the visual and musical content beforehand and performed by a lighting technician following a fixed plan.

In this example the scenographer once again takes on the role of an actor, even if spontaneous interventions can be reduced by pre-produced elements. The immateriality of media scenography grows in importance in this and comparable situations: it allows a direct reactive integration in live proceedings and thus has a plasticity that a classic design could not provide in this manner. At the same time, this was a basic prerequisite of the project, as the rather spontaneous, interdisciplinary encounter between live musicians and visual artists in a sold-out concert hall represents a gamble with considerable risks. As there was no prior contact between the musicians and the visual artists, the agency took on an important role as intermediary and communicator: the exchange between the two groups of artists took place almost exclusively via the project manager as well as their assessment of the cooperation. However, this concentration on one responsible person also brought new altered strategies of trust into play: this was not a group of interdisciplinary artists put together to deliberate and design collectively with experimental freedom and willingness to take risks, but rather a specialist in music management established the rules—as far as this was accepted from the artistic side—and, from the perspective of the promoter, a certain control and as such a reduction of risk linked to this. We were given almost complete freedom in this specific case, but there was a conservative factor in terms of structure, one that is particularly inherent in productions created by the cultural industry: risk reduction through recourse to tried and trusted methods, results and models, optimisation in terms of time and finance through structural division of labour, contractual regulations and obligations, including possible claims for compensation. The formation of trust on a personal level did make certain work processes easier, but was—when compared to free artistic processes—demanded much less in these production contexts. Creative work, which always contains something visionary and utopian, can only be emancipatory and delimiting towards such structures in order to assert artistic concerns and ideas.

⁵Chattin’ with Chet – the Chet Baker Story was performed in the T-Mobile Forum in Bonn in May 2008 in cooperation with Deutsche Telekom and the producer infocom.music ICM Cologne, under the project management of Marco Ostrowski. It followed on from the successful Percussive Planet event. Although conceptually completely different in terms of content and organisation, there were possibilities to build on the first concert. Baker’s life story, written by Marcus Woelffle, was read in sections by Uwe Ochsenknecht. The band was made up of Gerard Presencer (trumpet), Jim Watson (keyboards), Rob Taggart (keyboards), Tom Mason (bass), Winston Clifford (drums and vocals) as well as special guests Allan Praskin LA (saxophone) and Julian Wasserfuhr (trumpet). Responsible for the media

3. ROLL_OVER_BEETHOVEN

Artistic contributions to the International Beethoven Festival Bonn.

A continual cooperation with the International Beethoven Festival Bonn has developed since 2005 under the title Roll_over_Beethoven. While the first projects in 2006 had a mainly filmic character, concentrating particularly on the synthesis of media art and classical music, the intensive engagement with the theme in 2009 saw the creation of works that quite quickly left behind the scheme of sound and moving image, to take up approaches in spatial staging and installation. As the festival also sees itself, beyond its core theme of Beethoven, as a platform of interdisciplinary artistic engagement with music, and these endeavours were able to consolidate successfully over recent years, an additional suitable sphere is opening up here.

A trusting, cooperative partnership with the management and artistic directors of the festival has existed for years. The starting points of collaboration have thus far been specialist courses at the “Media Scenography” faculty, which, with the support of the artistic directors of the festival, offers interested students the possibility to engage intensively with Beethoven in dialogue with musicologists and practicing musicians. This encompasses both the interpretation of selected compositions and historical contexts as well as the life of Beethoven, collaboration with other art forms, but also iconographic aspects and musical themes in the international reception and marketing of Beethoven. There are no stipulations in terms of content, form and media.

As with all installation and scenographic work, the problem of suitable spaces arises. With the support of the festival management, our desire to be able to present as many of the works created for the festival as possible over the complete period of 5 to 6 weeks was fulfilled. The management of the Beethovenhalle was prepared to put the Kammermusiksaal and, when needed, the foyer at our disposal in 2006 and then again in 2009. In 2009, through the mediation of the director of the festival, the Bonner Kunstverein as well as the Kunstmuseum Bonn were also available for performances.

However, the communicative effort required as a trust forming activity also increases with the number of partners: as young artists can generally give no totally binding statements on the quality of their work in progress, where sufficient evidence is often missing, only positive intentions can be offered at first. Ensured forecasts on the quality to be expected and successful completion remain open. Intensive exchange involving all of the relevant partners through the working and development phases was therefore absolutely prerequisite to the formation of a collective basis of trust, which bridged and carried this relatively undefined period of orientation. As there were, to a large extent, no specifications in terms of contract or content, apart from the time frame—everything was thus still possible—a consensus could only be reached through gradual convergence, breaking down complexity incrementally: the undefined took shape through collective evaluation. In the advanced stages, exchange on the institutional level, which had initially been group-centred, was additionally individualised, so that every artist had their own contact person and could position their project in a most direct way. This rather person-based network of trust “on equal footing” progressively simplified flexible and swift decisions.

The development of an exhibit that can survive five to six weeks of audience attention or, in the area of media, is reliable enough to run for several weeks, from concept to realisation, requires 9 to 12 months in an educational context. The curricular structure of courses and the freedoms associated with this are therefore essential to the success of longer-term projects.

Five pieces of work were created as part of the course Media Scenographies Roll_over_Beethoven 2009: one performance and four installations. Three works in particular, which are especially close to the field of scenography, will now be examined in more detail.

3.1. MOONLIGHT SONATAS

RaumZeitPiraten: Tobias Daemgen, Moritz Ellrich. Optical, acoustic and electronic instruments, video, projections: performance, 30 min.

The artist group RaumZeitPiraten, Tobias Daemgen and Moritz Ellrich, use projection and lens systems they have built themselves in their audiovisual performances. These are often fanciful things, made of misappropriated items and found objects. The acoustic layer of their performances often involve modified toys and historical instruments as well as sounds created digitally. They opened the series of exhibitions Roll_over_Beethoven 2009 in the Kunstmuseum Bonn with a 30-minute inter-media performance based on Beethoven’s Sonata quasi una Fantasia. With their homemade, often bizarre looking optical-acoustic instruments, they staged various interpretations of the Moonlight Sonata—from a classical concert, via historical punched-tape coding and popular film music to a Game Boy version—to a variety of representations of the moon. Scientific drawings and historical illustrations were collaged with clips from documentary and feature films, artistic representations and adventurous fantasies. A significant component of their performance was the artistic action per se. Both artists worked—like media alchemists—in a wondrous laboratory of image and sound to create magical and poetical moments.

3.2. ARCHITEKTIQUE (Eva Kehl-Cremers)

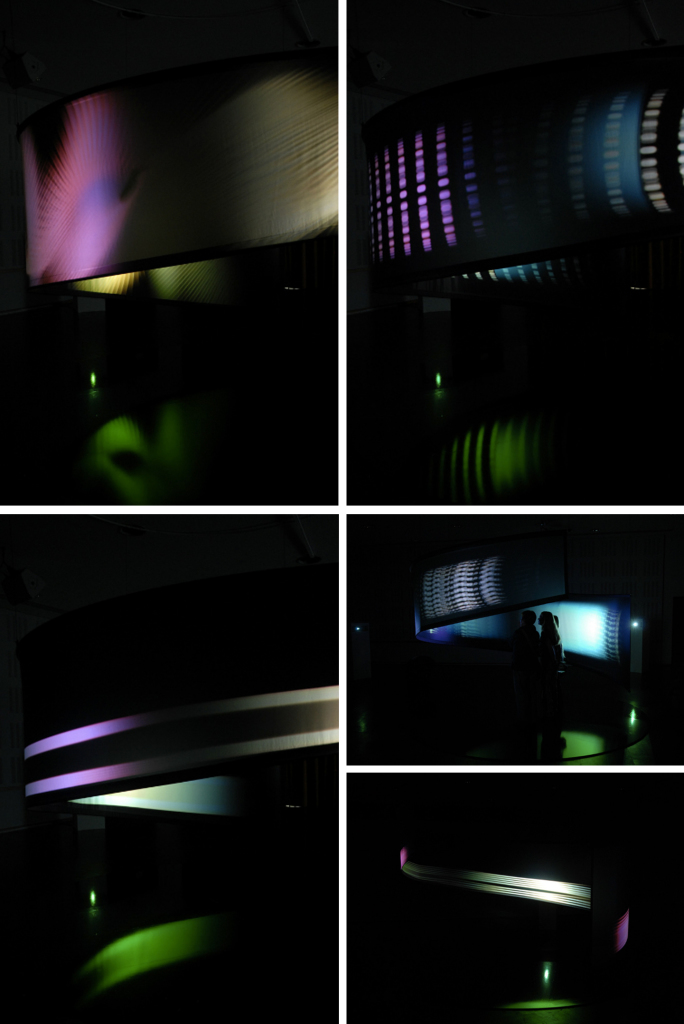

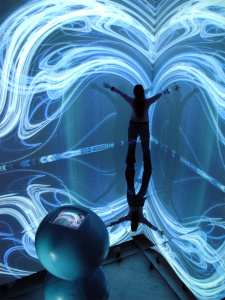

Immersive audiovisual space and artistic animation to Beethoven’s “Sonata Pathétique” in C minor, Op. 13: 3 beamers, sound, 3 mini PCs, helix-like projection surface, reflective floor.

Eva Kehl-Cremers decided to transpose Beethoven’s Sonata Pathétique into an immersive, spatial installation. Architektique is a helix-like audiovisual architecture that transfers the structural features of the musical composition into space, time and movement. The spiral that wound from the floor up to the ceiling was the projection surface for the musical animation, but also marked an opening, three-dimensional pictorial space, which could be both walked around and entered by viewers. In the core of the helix the viewer was enclosed by an image-sound space. A dark, slightly reflective floor surface inside the installation opened up a further dimension downwards, significantly reinforcing the illusion of optical-spatial integration. Architektique was open to the public in the Kammermusiksaal of the Beethovenhalle, primarily during various events.

3.3. ACTIVE (Jongwon Choi)

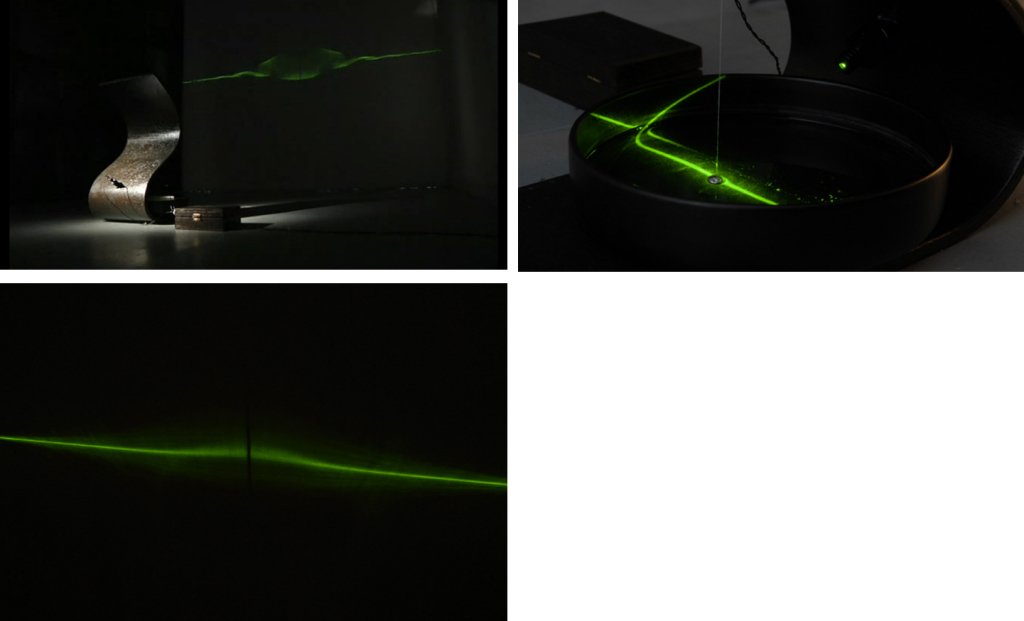

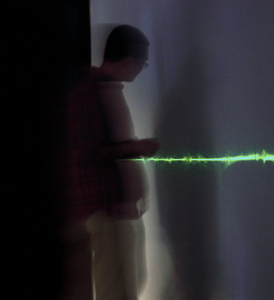

Kinetic installation: water, laser, wooden sculpture, sound, light reflection.

Jongwon Choi’s contemplative work Active exhibits a closeness to Zen. At the same time it is an allegory of the transformative cycle. The artist installed a wavy wooden sculpture, which housed a bowl of water and a mini laser, on the floor of a darkened room in the Bonner Kunstverein. Transferred via a pendulum, Beethoven’s Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in D Major, Op. 61 created wave-like reactions on the surface of the water. The concentrated light of the laser was focused on the water surface, reflecting these movements and casting them onto the wall as an optoacoustic photograph. In this way, acoustic waves were transposed into fluid material waves and then into optical waves. In a further step, these optical waves could again be restored into acoustic ones. This closed cybernetic system generated a poetic space of sound, light and ephemeral images.

4. PANTA RHEI

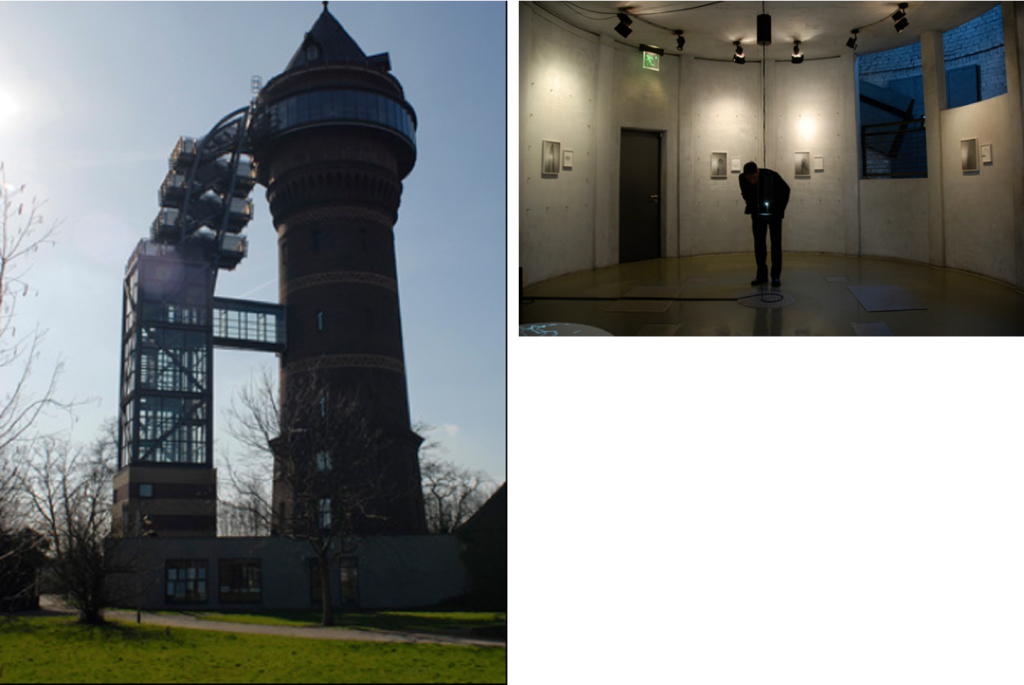

Exhibition cycle in Aquarius Wassermuseum.⁶

The multi-award-winning Aquarius Wassermuseum, a historic water tower by the river near Mühlheim an der Ruhr, is run by the energy company RWW/RWE. Over several floors, visitors engage with the fascination of water in its various guises but especially with its importance to agriculture and food, as a transport route and for industrialisation, especially in the Rhine and Ruhr district.

The first cooperation with the director and executives of the museum came about in 2004. A series of works were created that engaged mono-thematically, but with the most varied of perspectives, to water: its cultural, mythical and religious meaning, aesthetic and acoustic forms as well as social, climatic and economic factors. Alongside installations inside the museum and in its outdoor areas, further interventions were created, in cooperation with Stadt Mühlheim, in public spaces in the city centre. This first phase of the project can be seen as both a test and the first step in further collaboration based on trust.

⁶The exhibition cycle Panta Rhei took place in the exhibition area of the RWE’s Aquarius Wassermuseum in Mühlheim an der Ruhr from November 2005 to November 2007. The projects came into being as part of a course at the “Media Scenography” faculty, in cooperation with Heide Hagebölling as project manager and museum director Andreas Macat. The participating artists were Shinya Tsuji, Meike Fehre, Mohamed Fezazi, Zhe Li, Benjamin Wild, Helge Jansen, Vesko Gösel and Irena Paskali. The sound performances were by Fugi, Franziska Windisch, Helge Jansen and Earweego: Echo Ho and Hannes Hoelzl.

The exhibition cycle Panta Rhei followed on from November 2005 to November 2007. The main exhibition space on the ground floor of the water tower was made available to us for this period. Together with the museum’s management and a group of interested young artists and students, who came together to form a working group, we agreed on the thematic field, the spatial conditions and the temporal rhythm: every three months a new project would be presented to the public. Nine projects were realised for the museum in this period. Six pieces were discussed with the museum’s management in their conception phase at the beginning of 2006 and presented as drafts in a brochure. This acted as both the basis and the guidelines of an agreement for the clarification of important conditions concerning logistics, financial support, technical conditions and practical help in setting up and dismantling. The content and design of the respective exhibits remained unaffected by it. Due to the project’s long duration, these agreed, if somewhat “soft,” basic conditions proved extremely helpful and also freed up the creative process: concentration was on production, everything else was already consensus. Actual communication, and as such a certain formation of trust, was thus related to the artistic realisation and the openness to changes, rejections and reorientations, as are typical in the identification process. In principle it concerned stabilisation within the group, in other words a collective acceptance of subjective and individually chosen creative realisations.

In order to portray the results of this more closely, four works, which dealt in particular with spatial-scenographic aspects, will be introduced. As well as dealing with the phenomenon of water mono-thematically, space acted as a second constant: while the projects revolved around a common network of content, the staging of the various projects was determined be the specifics of the respective locations, such as the size and shape of the rooms. Three of the works also incorporated musical performances, composed especially for the respective project. As such the stagings expanded, beyond optical-spatial effects or the specific acoustics of the installation, to the dimension of musical experimentation.

4.1. WATER RING SPACE (Shinya Tsuji)

70 transparent sections of pipe, 4 water pumps, water bucket, sound modulators, light and shadow.

Shinya Tsuji opened the exhibition cycle Panta Rhei in November 2006 with his spatial installation Water Ring Space – circular flow of being. In Buddhist and Taoist philosophy, circular flow—ri-ne ten-syo in Japanese—embodies continuous coming and going. This forms the foundation of numerous works by the artist.

Channelled through 70 transparent tubular elements, water flowed from the upper floor of the historical tower, along the facade, traversing the exhibition floors before being pumped back to the top of the system. Light and shadow effects created an ephemeral doubling, amplifying the spatial impression. The various lengths of pipe, and in particular the shape of the end piece, out of which the water flowed, created acoustic resonances and rhythms, filling the space with harmonic, decidedly contemplative tonal shapes. The opening of the piece was marked by the musical improvisation Stück für einen Wasserkreislauf und Flöte by the artist Fugi and an accompanying Japanese tea ceremony.

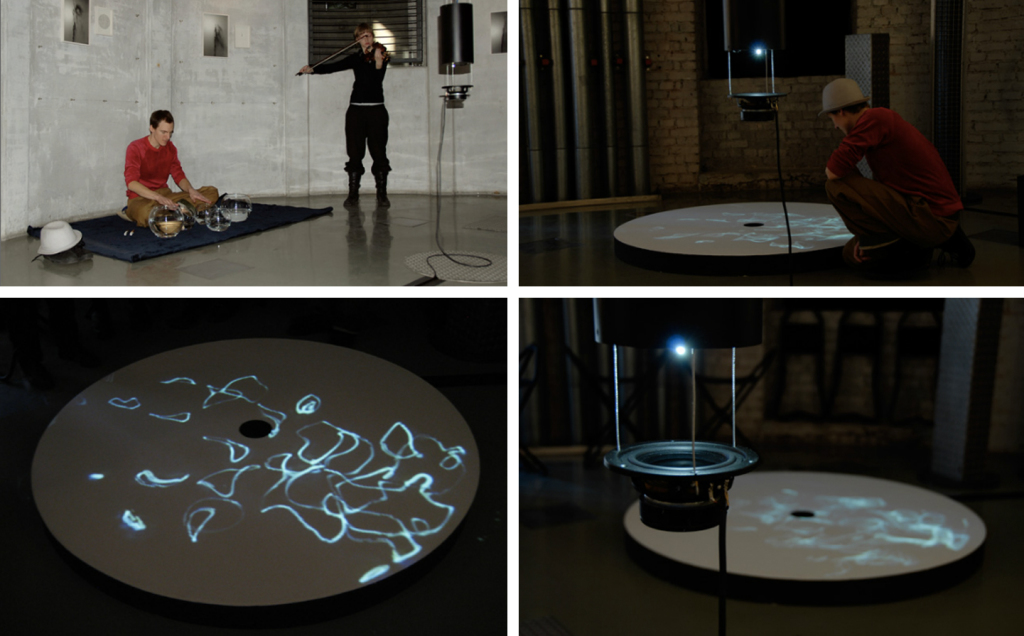

4.2. SWINIGING MATTER (Helge Friedrich Jansen)

Cybernetic installation: electromagnetic field, closed-circuit video, video projection on a plate on the floor.

At first glance, Helge Friedrich Jansen’s installation Swinging Matter resembled a laboratory set-up for the demonstration of physical principles, making visible the effect of vibrations in the room on the behaviour of the water surface. The viewer changed the electromagnetic sphere simply by entering and leaving the exhibition space, and thus became an active factor in the energy field. Helge Jansen employed these physical changes by transferring the fluctuating values onto the surface of the water via a membrane. A video image of the water surface was then projected onto a round plate on the floor. Calligraphic symbols and notations like abstract poetry were created according to the pattern of the visitors’ behaviour and movement, translating the immaterial phenomena of the space into something visual. Jansen was particular interested in the fact that unintentional human intervention became part of the artistic spatial staging. He also expanded his notion of space to include an acoustic dimension, performing, with violinist Franziska Windisch, the composition Ohne Titel: Improvisationen für Wasserklang und Violine for the opening of the exhibition.

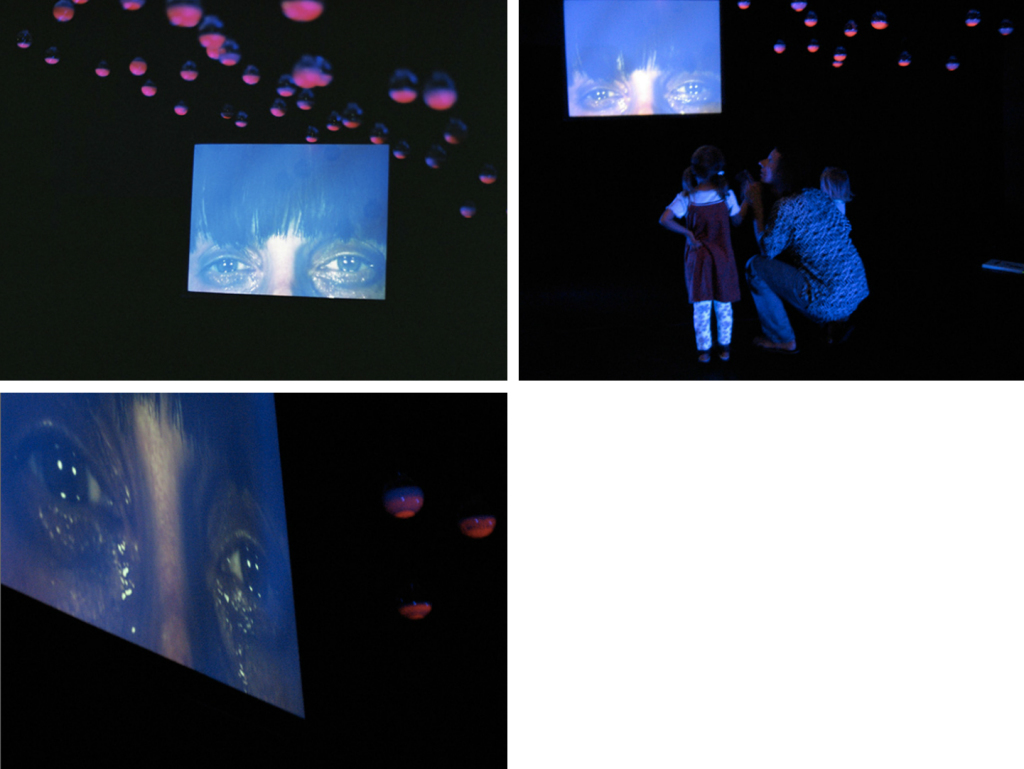

4.3. SALTY DROPS (Irena Paskali)

Installation with glass vessels, luminescent liquid, black light, video projection and sound.

In Salty Drops, Irena Paskali picked up on emotional and ritual meanings, as referred to in the Odyssey and the myths and sagas of antiquity. Joy, fear, pain: tears express the deepest of feelings. When they run dry, they leave behind crystals. It is said that the women of antiquity collected their tears of fear and loneliness in small vessels, in order to show them to their husbands once they returned from military campaigns and adventures. Irena Paskali transferred this gesture into a contemplative spatial scenario: filled glass vessels hung in the darkened room like drops, on the back wall the teary eyes of the artist, accompanied by the sound of solitary drips of water. The artists Earweego, Echo Ho and Hannes Hoelzl, developed the performance Opaque Liquid Space especially for this scenario, accompanied by a suikinkutsu (Japanese water harp), synthesized drips of water and vocal fragments.

4.4. FLUID MUSIC (Zhe Li)

Interactive space: digital animations, digital sound, reflective floor, double projection, 2 beamers, PC, touch screen and display.

The artist and designer Zhe Li works primarily with interactive installations. The viewer as participant and experimentation with intuitive interfaces, which he often develops himself, are thus the focal point of his interest. A further characteristic, which is found increasingly in more recent works, is the engagement with and creation of playfully communicative situations.

With his installation Fluid Music Zhe Li created, for the first time, a hybrid audiovisual space with playful accents. Water sounds—dripping, rain, tropical downpours, rivers and waves—together with corresponding images, created an immersive, fluid environment. Visitors immersed themselves in the virtual scenography via an intuitive interface, generating compositions of image and sound. One of Zhe Li intentions was to animate groups of visitors, especially children and young people, into having a collective experience.

CONCLUSION

The artistic examples presented in this article are scenarios of themselves—they refer to themselves and are as such essentially self-involved. Here the question of trust is particularly relevant in the creative phase. As such it refers to an analytical consideration of the production of art and thus to the function of trust in certain contexts and under special conditions. Art, as a system that creates what is initially chaos and discards that which is known, is especially dependent on the formation of trust. Artistic work wishes neither to inspire superficial trust nor to stage trust—but is all the more bound to it in the process of its creation. Staging—as a component of artistic production—and trust are actually inseparable.

The staging of trust is located essentially on the intersection to the public sphere and also marks out the difference to the arts. The staging of trust is generally intentional and done for a specific purpose. It can only take place on the level of a cultural code that is superimposed on the message, which is thus suitable for the masses and the media, and is, in certain situations, associated with a danger of slipping into cliché. Public communication without staging is no more possible than non-communication itself. These mechanisms are equally true in the art market: the moment that art obtains other functions and contextual attributions beyond itself, it becomes an object of the staging of trust. The museal environment of the museum and presentations in galleries are as subject to this as the critique of art, media reports, the results of auctions and the growth in cultural tourism.